INTRODUCTION

So far as I know, I first heard Peter Gabriel’s song entitled “Solsbury Hill” about a year ago. It’s been around somewhere in the background of my awareness, of course, for roughly fifty years. But I’m not sure if I ever actually “heard” this song before now with any depth of awareness.

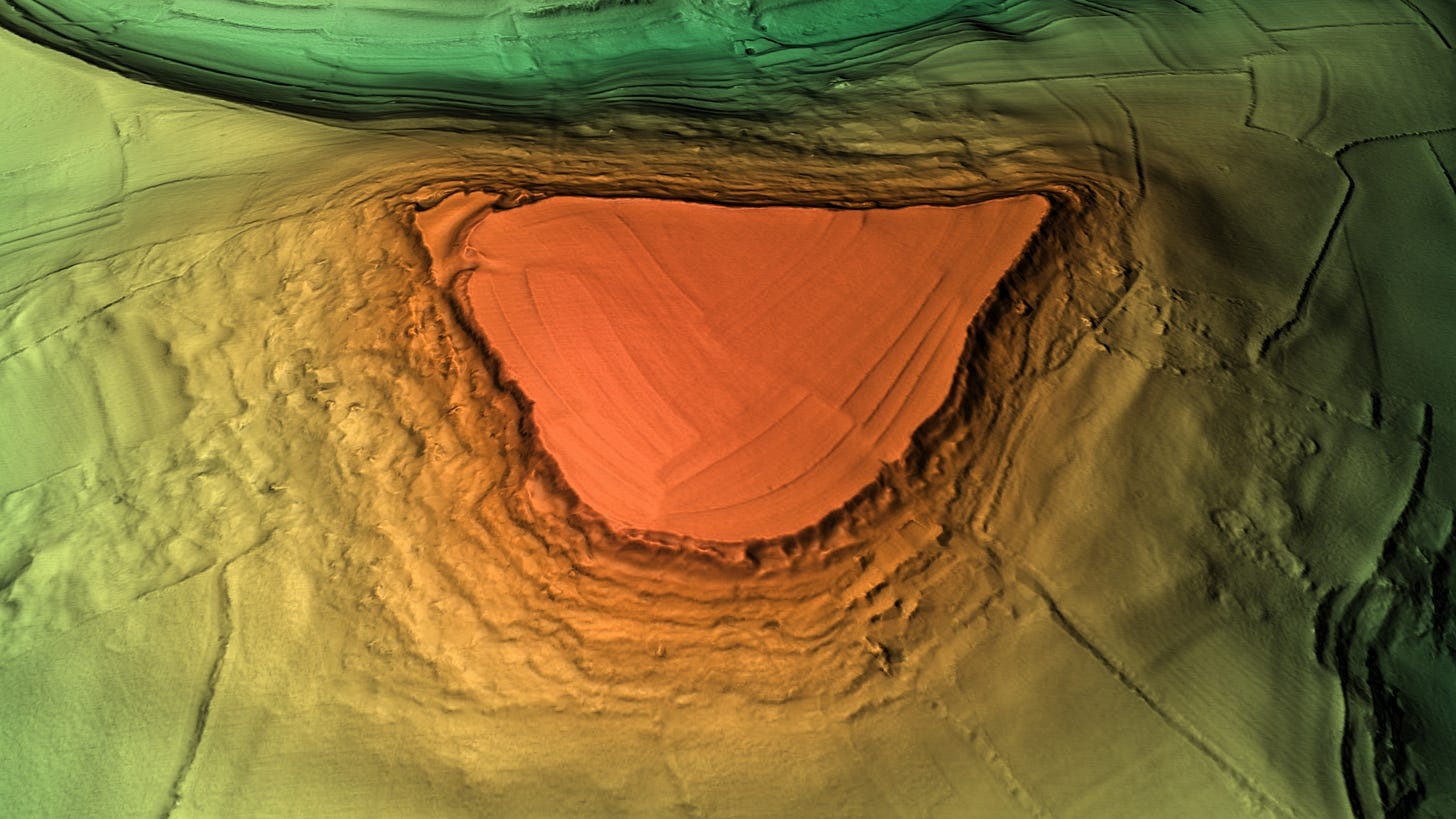

Because of my work with mystical qualities of ancient hills and mounds, what first grabbed my attention when I recently returned to the song in the Spring of 2022 was its title. I knew intuitively, before even paying attention to the lyrics, that this must be quite a magical hill— one that Peter Gabriel had been drawn to because of its energetic signature, its geomantic lure, even if it was possible that he might not have been aware of this power. I have no clue, of course, what he was actually thinking when he chose this particular hill as the focus of this energy meditation but, being one attuned to such attractions to earth portals myself, I could tell that this power called to Gabriel for some time before he composed “Solsbury Hill” itself.

Once I had actually listened deeply to the song’s lyrics over and over again and read some of the critical accounts concerning its significance during a key moment of transition in Gabriel’s life, I was and was not surprised to learn, then, that Gabriel was clearly well aware of the power of this ancient site.

One of the things I have imagined for this Soul Planet Channel space is a chance to write more off-the-cuff pieces growing out of undeveloped moments of inspiration. I had such hopes when I began writing this essay back in July of 2022. Even so, perhaps due to being a professional academic for forty years, as well as a musician, I have become wedded to the notion that my public writings need to be final, polished, set in stone. As it turns out, I had way too much to sort through in my exploration of this song to allow for a free-flowing track of off-the-cuff inspiration. The technical and mystical complexity of the song sucked me in and forced me to attend to the deep, deep layers of its texture. So, I guess in the end there is nothing casual in my relationship with the song.

The journey recorded within the song became the catalyst for my own journey in relation to the song. I will try to point to key aspects of my personal journey into “Solsbury Hill” by examining, first, some external notes on the hill itself; second, my reading of the transformative story in its lyrics; and finally, a deep dive into the musical structure of the song as the music itself mirrors the mystical journey recounted in the lyrics.

I am Gabriel Hartley, and this is episode number 51 of my Soul Planet Channel for the 17th of December 2022. I have entitled today’s episode “Climbing Up on Solsbury Hill: The Geomantic Song of Peter Gabriel’s Mystical Initiation.”

As with all forms of social media these days, if you like this post, please hit the like buttons, share it with your friends, and become either a free or paid subscriber. In this way you can help make this material available to a wider and wider audience and give me a sense of your engagement and enthusiasm.

If you wish to help me out in this work but don’t wish to sign up for a paid subscription yet, you can make a one-time donation to this project by clicking the “Buy Me a Coffee” link. In any case, thanks for being here and reading and/or listening to my message!

PART ONE—THE GEOMANTIC NATURE OF THE HILL

So far as I know, I’ve never been to Solsbury Hill in this life, although I have been close by a few times. As a substitute for my actual physical presence there, I’ve been exploring web sites related to the geomantic qualities of Solsbury Hill, such as the website entitled Earth Acupuncture in Context. This particular website provides case studies of places that reveal certain degrees of Geomantic Stress. They explain the relationship between Geomantic Stress and Feng Shui as follows:

Geopathic Stress ([or] GS) and Earth Acupuncture have always been an integral if esoteric part of Feng Shui practice. Where the Feng Shui form of a building or landscape is poor, the effects of GS will be worse. Where a GS line runs across or through other key points in a property besides the bed, such as the front door, front gate, or centre of a house, the quality of Qi entering the property will be compromised and the whole building will suffer. [Endquote]

Their case history involving Solsbury Hill says the following:

Following the cutting of a by-pass, through the shoulder of Solsbury Hill, to the north-east of Bath in 1995, the city experienced a dramatic economic decline, with many shops and small businesses closing down. The suburb of Larkhall had its first ever outbreak of burglary and vandalism.

Dowsing revealed that two major Dragon veins had been severed on their course from Solsbury Hill, through Larkhall, to Bath Abbey and the Circus respectively. In May 1996 four sandstone Cairns were raised on either side of the road cutting, on the mid-lines of the earth meridians, aimed at restoring the flow of Qi across the road cutting. Local feedback confirmed that Larkhall’s crime outbreak ended the following week as suddenly as it had started, and Bath’s economy had picked up within a month. [End quote]

I visited Bath in 1977 as an exchange student in London. At the time, I found the city—and the Roman baths after which it is named—intriguing, charming, attractive, but I hadn’t picked up on any esoteric resonances. Not much longer after my trip to Bath, I visited the much more famous site of Stonehenge, although even there I wasn’t yet predisposed to pick up on its infamous energies. Even so, during that Fall I did have my first Akashic visions of ancient histories and practices in Wimbledon Common, just across the street from where my college was located—but I have never heard of anyone else picking up on the geomantic and Druidic energies of that place.

My personal introduction to the ancient magic of Bath came in my reading of Leslie Marmon Silko’s novel Gardens in the Dunes. I will write at length about this book at another time, but for now I’ll just mention that in the novel, Silko—an American Indian from Laguna Pueblo, New Mexico—focuses on a young Indian girl from the Death Valley area as she travels through Europe around the year 1900. During those travels the girl learns about the indigenous tribal practices of Europeans. Bath was the location of her first experience of this ancient history and its continuing resonances in the present. Upon reading this novel, the indigenous shamanic roots of Europe suddenly rose up into my consciousness and transformed my own life.

The Wikipedia entry on Solsbury Hill tells us that the name “Solsbury” “may be derived from the Celtic god Sulis, a deity worshipped at the thermal spring in nearby Bath.” The entry goes on to say:

Solsbury Hill was an Iron Age hill fort occupied between 300 BC and 100 BC, comprising a triangular area enclosed by a single univallate rampart, faced inside and out with well-built dry stone walls and infilled with rubble. The rampart was 20 feet ([or] 6 m) wide and the outer face was at least 12 feet ([or] 4 m) high. The top of the hill was cleared down to the bedrock, then substantial huts were built with wattle and daub on a timber frame. After a period of occupation, some of the huts were burnt down, the rampart was overthrown, and the site was abandoned, never to be reoccupied. This event is probably part of the Belgic invasion of Britain in the early part of the 1st century BC.

[. . .]

The hill is near the Fosse Way Roman Road as it descends Bannerdown hill into Batheaston on its way to Bath. Solsbury Hill is a possible location of the Battle of Badon, fought between the Britons (under the legendary King Arthur) and the Saxons c. 496, mentioned by the chroniclers Gildas and Nennius. The hilltop also shows the remains of a medieval or post medieval field system. [Endquote]

As you can see in these various historical and geomantic descriptions, the hill that serves as the locale for Peter Gabriel’s visionary initiation experience is imbued with exactly the sorts of magical powers that one expect for such an account of transformation.

PART TWO—STORY OF INITIATION

The hill called Solsbury Hill first came to my attention via Peter Gabriel’s song. For me, at least, his song not only captures the magic of the place, but also captures the kind of awareness one needs to tap into the power of such places, a power that weaves itself into our consciousness and our mystical experience. So I want to explore the ways the lyrics and movements of the song are influenced by the power of the actual hill.

In order to follow along with my exploration of the song, you should listen to the recording at least a couple times beforehand. You can find it on the YouTube link I have provided:

The lyrics begin with the following statement: “Climbing up on Solsbury Hill.” The footsteps of this climb mirror the three lilting guitar notes of the opening partial measure, and in this way the music and the lyrics of the song are drawn together. Here is a sample of two measures of the guitar music: [audio file].

This upward musical ascent is the necessary prelude to the protagonist’s initiation on the hilltop. From up there he can look out over the village and tell us: “I could see the city light.” The speaker has withdrawn from the civic boundaries of his community in order to observe his surroundings and open himself up to other forces: “Wind was blowing, time stood still.” Let me sing the first half of the first verse in order to lay this out:

Climbing up on Solsbury Hill

I could see the city light.

Wind was blowing, time stood still.

Eagle flew out of the night.

Notice how Gabriel moves down the musical scale as his attention drops from the hilltop down to the city and out across the expanse of the area.

Up on the hilltop, open to the forces of change now blowing around him, the hero steps out of the typical cycles of time into a moment of eternity. In the words of Joseph Campbell in his infamous book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, “[T]he hero as the incarnation of god is himself the navel or axis of the world, the umbilical point through which the energies of eternity break into time” (38) [endquote]. I discuss Campbell’s points concerning this topic in my earlier post from the 9th of June 2022, entry number 31 entitled “The Vedic Roots of Joseph Campbell’s Dance of Eternity and Time.”

Before the hero of Peter Gabriel’s song can become such a god, however, he must pay attention to the clues and invitations he sees up on the hilltop. This process grows on the speaker when, after noticing the blowing winds and the stoppage of time, he sees his next transformational clue: “Eagle flew out of the night.” Given the rarity of eagles in Somerset, England, this itself is a clue that the speaker is entering a rarer dimension of perception than he was able to experience down in the city lit below. Just four bars into the lyrics of the song, the hero is prepared for a process of engagement with his higher powers.

As the second half of the first verse opens, we hear “He was something to observe.” Now, given that so far the only other being in the song has been the eagle just mentioned, we might at first assume that this “he” refers to the eagle. But it quickly becomes clear that this “he” is someone or something that confronts the hero and speaks to him: “Came in close; I heard a voice.” The speaker has been captured, awestruck in this moment of revelation as he says, “Standing, stretching every nerve, / Had to listen, had no choice.”

What our hero is told is utterly mysterious, as we see when he confides that he “did not believe the information.” Even so, he “just had to trust imagination.” At the height of this excitement—“[His] heart going boom, boom, boom”—his unexpected guide tells him, “Son, . . . grab your things, I've come to take you home.” Through this imaginative transformation and an instinctive trust, the hero engages in a homecoming journey. He has been initiated into a higher sense of Self.

The second verse of the song informs us of the consequences of fundamental personal transformation. We see that such initiations rarely bring immediate peace of mind, for they often involve such a dramatic transformation of one’s self-concept that the hero can rarely if ever remain connected to the people, the values, and the rhythms of life that had formed the basis of his previous version of Self. Gabriel’s hero resigns himself to silence, knowing that speaking openly about such experiences would most likely appear insane. Many of us who have spoken of such transformative experiences have also met with such disbelief and rejection. Any such “turning water into wine” would soon leave us on the outside of the bounds of social acceptability. Yet this growing sense of alienation and alterity highlights the mind-numbing repetitiveness of daily life, emphasizing the need to cut connections with those who can no longer make sense of us in the terms of our new identity.

But the benefits of this separation bring about a newfound larger sense of connection with one’s planetary nature: “I was feeling part of the scenery / I walked right out of the machinery.” The initiate experiences a release from the mechanical ties that bind us, a release emphasized by the return of the hero’s boom-boom-boom beating heart and a renewed call by his Higher Self to grab his things and follow his guide back home.

The third verse focuses on a third stage of revelation and release. From the mystery of the first verse to the dejection of the second, the third verse now strengthens the hero’s newfound awareness that the traditional definitions of social freedom are based on illusion, that our previous friends and relations now appear as “empty silhouettes,” their closed eyes appearing to them as true and proper vision. The hero of initiation, eyes now open, has found an unexpected source of strength and confidence in his new self-definition: “I will show another me.”

The third chorus, then, highlights a new sense of strength in the completion of the initiate’s transformation. He has accepted what he now recognizes as his true self: “Today I don't need a replacement / I'll tell them what the smile on my face meant.” By the time the beating heart goes boom-boom-boom for a third time, the initiate has accepted this mystical invitation to a higher sense of connection: “Hey, I said, you can keep my things, they've come to take me home.”

PART THREE—THE MUSIC OF THE SONG

This next section will be difficult for me to convey accurately in speech because I am using a lot of visual aids to make my points about the scoring of Gabriel’s song “Solsbury Hill.” I urge you either to follow along with the online text of this post or to go back to the text after listening to the audio version of my podcast. Now, back to my story of the song . . .

What I realized, after spending a lot of time figuring out exactly what is happening musically in the song, is that the lyrics perfectly match the song’s architecture—or vice versa. By the time the first words are sung, the instrumentation has already taken on a magical, compelling life of its own, so much so that it that grabs the listeners by the collar and carries them away in its rhythmic and sonic fluid complexities. That means, then, that I should now look into what’s going on in the introductory bars.

As you heard earlier, “Solsbury Hill” opens with a haunting guitar riff that serves as a refrain throughout the song. A good sampling of this riff appears in a YouTube video from Malero Guitar. Not only does this guitarist give us a close-up view of the fingering on the frets, but he also gives us a point-by-point scoring on the tablature that serves as his video’s backdrop.

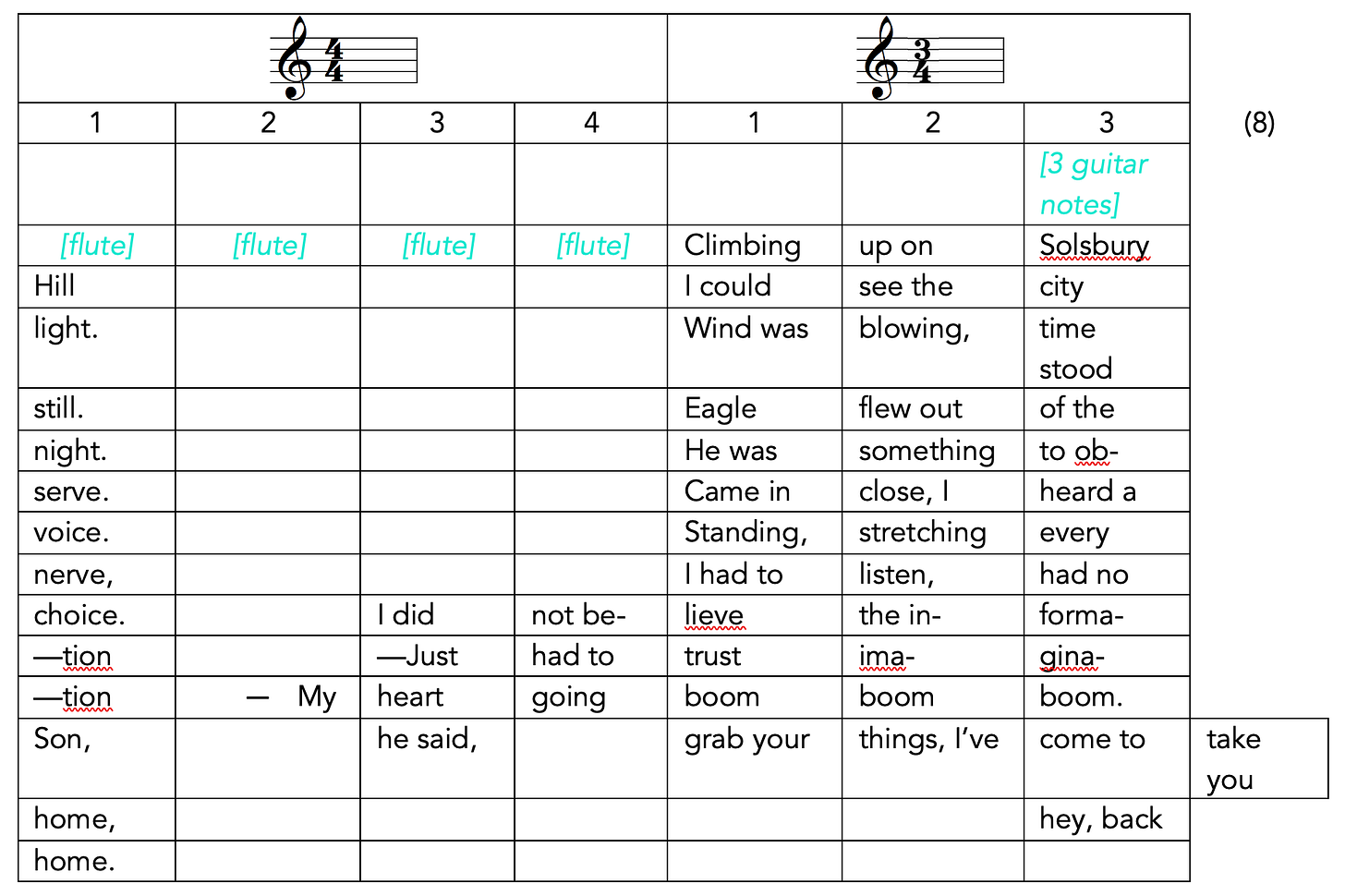

The rhythm of each full measure involves two discrete segments, the first made up of four beats (sounded by the flute) and the second made up of the three-beat pulse lyrical section, combining to fill out the 7/4 time unit of each complete musical line.

In the segment of the sheet music that I have included above, notice the three notes—shaded in yellow above—that open the song in the first partial measure (an opening musical segment that is known as an anacrusis or a pickup measure). This trio of notes, opening on the seventh beat of an as yet unplayed measure, gives the whole song a kind of in media res motion, giving us the sense that we are already in the thick of things before we could even be conscious of beginning. I argue that this opening-in-the-middle-of-things sensation structures our entire experience of the song, preparing us for the sense of being carried away by the mysterious stranger that Gabriel’s protagonist meets on top of Solsbury Hill. Also notice that these three notes are repeated as the measure simultaneously comes to a close (in yellow once again) and swings us back into the onward flow of the next measure, a repetition of the first. We come to realize as a result of this repetition that the opening three notes of the song are already a repetition, it seems, of a previously unheard or ultimately forgotten rhythm of experience.

After the six repetitions of the opening guitar riff that serves as the backbone of the entire composition, we can see that the song is then made up of three primary sections, each section made up of a two-part verse and what passes for a chorus, even though these choruses don’t repeat each other word for word as we would expect. The opening two lines of each chorus introduce new elements until the final two lines resolve into a normal repetitive structure.

INTRO 25 seconds long (Triad LEAD-IN 1 second; 6 GUITAR LOOPS each 4 seconds)

VERSE 1a: 4 bars, 16 seconds; VERSE 1b: 4 bars, 16 seconds; CHORUS 1: 16 seconds

INTERLUDE 1: 2 GUITAR LOOPS, 8 seconds

VERSE 2a: 4 bars, 16 seconds; VERSE 2b: 4 bars, 16 seconds; CHORUS 2: 16 seconds

INTERLUDE 2: 2 GUITAR LOOPS, 8 seconds

VERSE 3a: 4 bars, 16 seconds; VERSE 3b: 4 bars, 16 seconds; CHORUS 3: 16 seconds

OUTRO [3:20-4:22]

Parsing out the 4/4 time segments from the 3/4 segments for the verses is difficult at first, but I have written up an approximation here, taking into account the slurring of notes from one measure to another. Notice how the first segment of the measure is parsed out by the flute (doo-doo-doo-doo) before moving on into the 3/4 segment of the lyrics: “Climbing up on Solsbury Hill.” The word “hill” has slid over from the first measure into the next measure as the word acts as the primary pulse note of the new measure:

Even more difficult for me to hear at first was where exactly the beats fall in the chorus lines. The final lines of the verses slide immediately into the flow of the chorus sections. In the example that follows, the verse ends when Gabriel sings “I had to listen, had no choice” before leading into the chorus line “I did not believe the information; just had to trust imagination.” I have created a visual snippet to illustrate this feature:

The compressed staccato nature of the chorus lines is in marked contrast to the lilting flow of the verses that move along with the guitar and the flute. These local complexities led me to create a visualization to help me see the overall architecture of the song as a whole.

SOLSBURY HILL MEASURES

In order to depict the beats per measure for the song, I created a table in which each row equals one measure (or bar) and each column equals one beat. Gabriel breaks each 7/4 measure into two segments, opening with a 4/4 beat followed by a 3/4 beat. Each measured phrase breaks before the final word. That word then swings over to serve as the opening beat of the subsequent measure. In poetry, the lines would be marked with a foreward slash, “Climbing up on Solsbury / Hill . . . .”

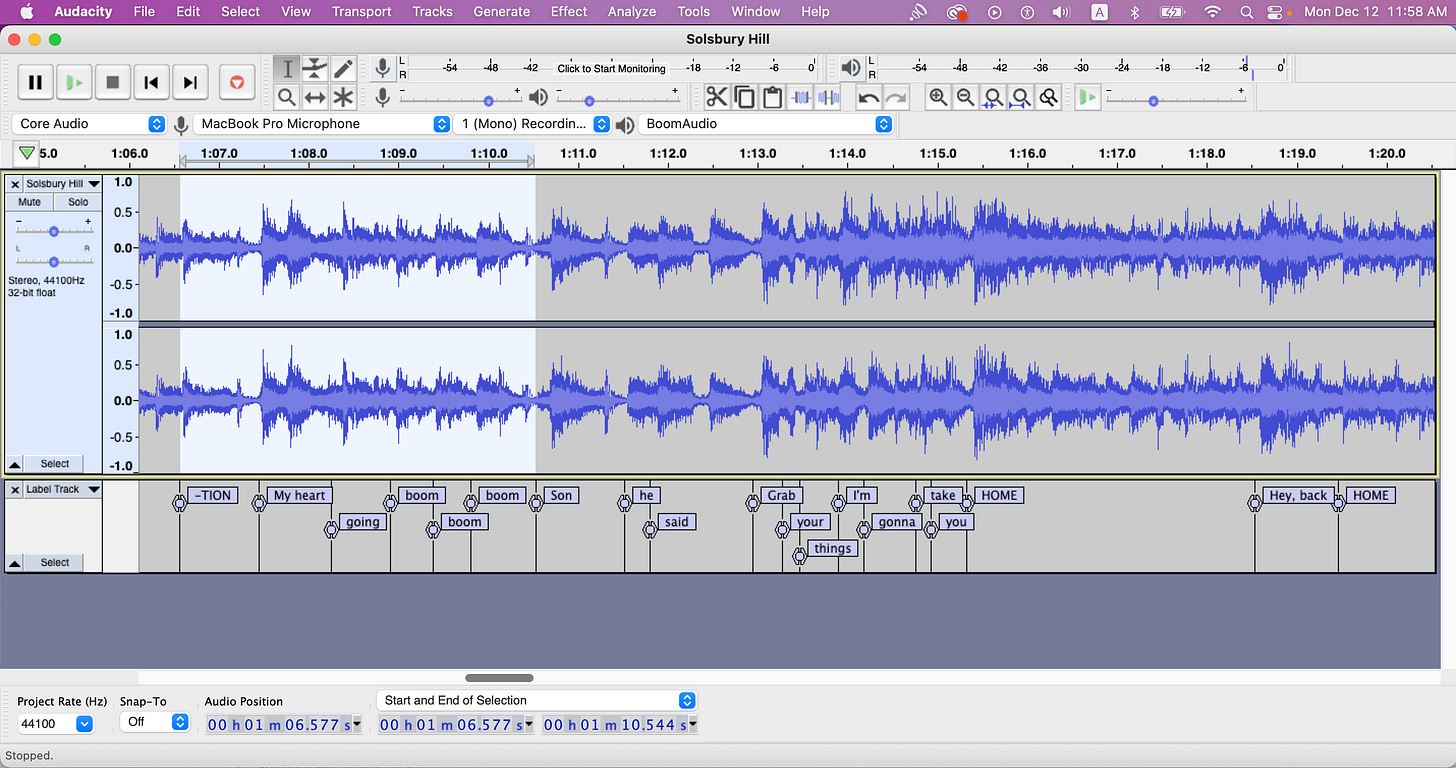

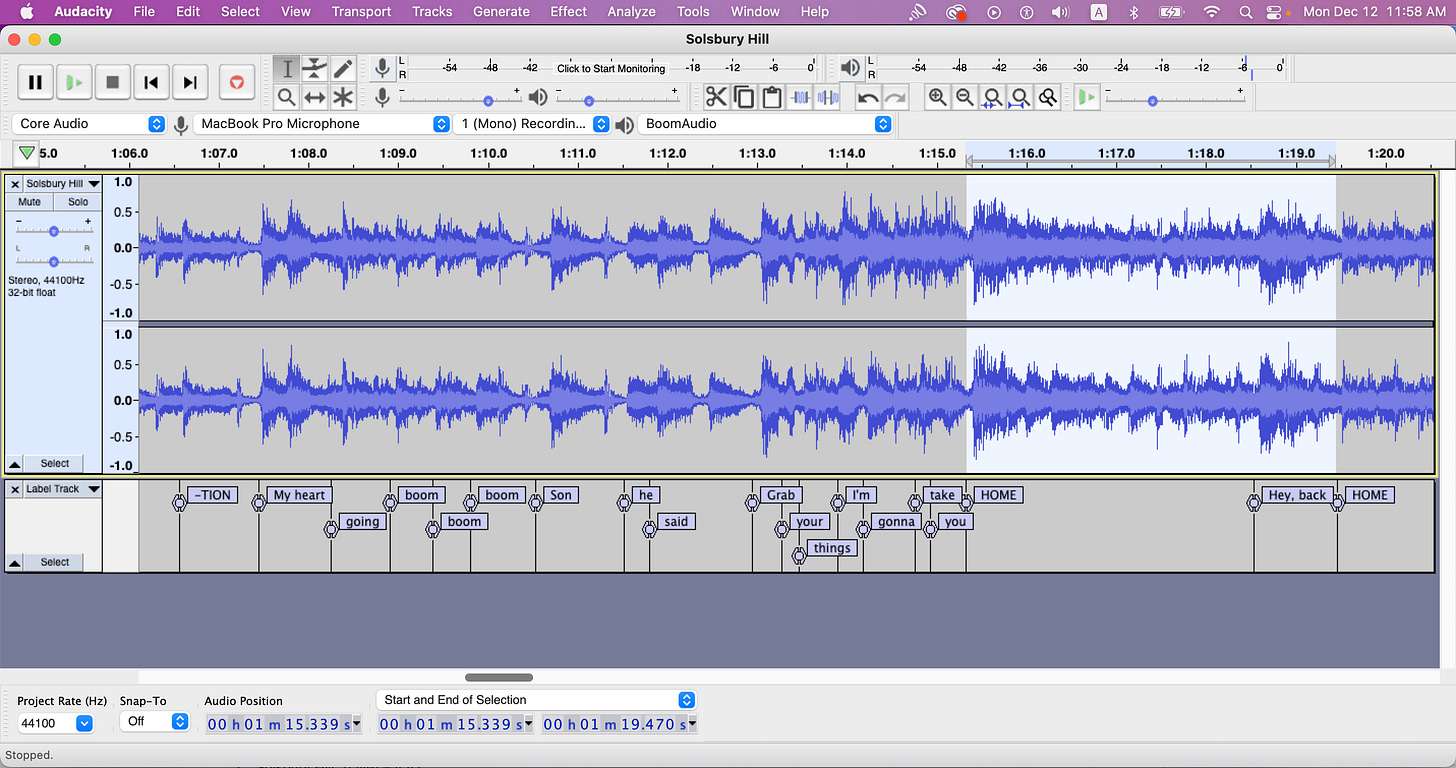

The most puzzling aspect of the song was the confusion created by the rhythm of the chorus line when Gabriel sings, “Son, he said, grab your things, I’ve come to take you home.” With the beats of each measure marked out as I have done here, we can see more clearly how the disruptive caesura effect of this line involves a surprising momentary switch from 7/4 time to 8/4 time. Another way to visualize this expansion of time in the line is by marking the measured time spans in the graphic tool of the audio application called Audacity. We can see there that the 7/4 measure for the line lasts for approximately four seconds:

The disruptive 8/4 measure, on the other hand, takes roughly five seconds:

But the measure that follows brings us back to the recognizable four-second flow of the 7/4 time signature:

This local disruption of the 8/4 measure is actually the consequence of the earlier disruption created by the boom-boom-boom of the hero’s stimulated heartbeat that forces the rhythm of the measure to pause, to break, to extend itself beyond the predetermined beats that otherwise regulate the song.

In fact, the booming heart is itself catching up to the disruption created by the staccato interjection of “I / did / not / be- /-lieve” into the lines when the chorus takes over. Whereas in all previous measures we have just one dominant beat per measure—the opening beat of each measure as the phrase spills over from the closure of the previous line, as with “hill,” “light,” “still,” “night”—we now have two alternating dominant beats per measure: the spill-over first beat AND the newly introduced beat that now opens the 3/4 segment of each measure: “I did not be-LIEVE” and “Just had to TRUST.” A spill-over half-beat caesura isolates the final syllable of each of the progressive nouns—“forma—TION,” “imagina—TION.”

As a result, we are left dangling until the second dominating beat anchors us back into the rhythm. Then suddenly the staccato heart-boom line comes to a stunning halt with the word “son” as it hangs there, mimicked by the isolated phrasing of “he said” until the hero is told “Grab your things. I’ve come to take you home.” The addition of the eighth beat projects us upward on top of the jangling jumble of staccato and stop of the chorus so far. Just like the hero of the song, we are snatched up skyward by the dragon of transformation, only to find ourselves brought back down to the home we forgot we had earlier lost as we ease back into the 7/4 rhythm.

I have gone into this much detail in describing the musical texture of the song because my engagement with the lyrics cannot be separated from my captivation by the rhythm and syncopation of the music. It was the music of the song that carried me away into my own mystical reverie before I ever actually listened to the story of initiation related in the lyrics. The song serves as a portal, giving me the chance to engage with the energies of Solsbury Hill from here in Fiskars, Finland. I hope that my exploration of these dimensions of the song has provided you with the possibility for a similar engagement with the ecstasy that entwines song, spirit, and place.

Intro— “Kind of a Party” by the Mini Vandals;

Interlude 1— “Float” by Geographer

Outro— “Read All Over” by Nathan Moore

postscript: MISCELLANEOUS NOTES

Several critics have spoken to the way each element of the song contributes to its mysterious captivating quality. We learn in Wikipedia that Peter Gabriel’s song engages his “spiritual experience atop Little Solsbury Hill in Somerset, England, after his departure from the progressive rock band Genesis, of which he had been the lead singer since its inception.” I will explore below just how much of this spiritual experience for me grows from out of the song’s haunting lyrics, but first I’ll point to comments from David Wilcox when he was interviewed by Matt Kohut on his Sounds Out of Time show:

First of all, it's in 7/4 time: bam bam bam bam bam bam bam [singing the guitar loop]—you got three (bam bam bam) and four (bam bam bam bam). So it's a bar three and a bar four. It's in 7/4time, and to make that sound natural, to make that sound easy, you have to abide in that and see what works. And then the rhyme scheme is so incredibly complex, yeah, like uh [singing] “to keep in silence I resigned / my friends would think I was a nut / turning water into wine / open doors would soon be shut / so I went from day to day / though my life was in a rut / till I thought of what i'd say / which connection I should cut.” Wait a minute! What the hell did he just do?! He rhymed the same rhyme through two of those four line little phrases, and there were inside rhymes. So that's like one two three four five six seven eight rhymes in those eight lines, and yet each phrase is a complete thought. Each phrase needs a pause after it. Each phrase progresses the story. There's no filler, there's no junk, there's no cutesy little crap extra syllable that rhymes.

In “10 Reasons Peter Gabriel’s ‘Solsbury Hill’ Is One of the Greatest Songs of All Time” Andrew Unterberger works his way through the ten features of the song that for him are so captivating. Again, the haunting nature of the 7/4 time signature draws our attention:

The 7/4 stomp of “Solsbury Hill’”is one of its indelible and striking features, that feeling of a beat missing in every measure giving the song a constant sense of struggle — and subsequently, of endurance. The fact that it’s always noticeable but never distracting is a tremendous accomplishment for Gabriel as a songwriter, and makes “Solsbury” a standout from the very beginning.

But just as important for Unterberger is the song’s moving guitar structure:

Part of the reason the song’s unusual time signature works is because it’s all in the guitars — that gorgeous spider web of an acoustic riff (played by Lou Reed and Alice Cooper guitarist Steve Hunter) circling the song’s perimeter and providing its pristine, immediately recognizable framework. But if the guitars are undoubtedly the blood pumping through “Solsbury Hill,” it still all stems from the beating heart of the drum thump, steady throughout, keeping the song even-keeled, marching forward and undeniably alive.

Closely related to the magnetism of the guitar riff, Unterberger claims, is

There’s not really a chorus to speak of in “Solsbury Hill” — a melodic shift at before the last four measures of each verse signifies the arrival of some kind of refrain, but there aren’t many repeating lyrics, except for this line, which shows up in each of the three verses. (If you were to try to identify “Solsbury Hill” to a friend, you’d undoubtedly either try to sing the guitar riff or this lyric.)

But the aspect of Unterberger’s analysis that moves us on to my own dive into the song are his comments about the scene-setting of the song:

Not even Martin Scorsese establishes the shot this well: “Climbing up on Solsbury Hill/ I could see the city light/ Wind was blowing, time stood still/ Eagle flew out of the night.” Doesn’t matter if you’ve never been within 500 miles of Somerset, England — with those 28 opening syllables, you’re right there with Gabriel, sharing in his moment of revelation. It’s the first and only time the song’s titular location is mentioned, but the mental image it invokes is burned in your mind for well longer than the four-minute runtime.

https://www.billboard.com/music/rock/peter-gabriel-solsbury-hill-anniversary-greatest-song-7702117/

Share this post